The Uncomfortable Patient

You are reading Ask The Patient by Dr. Zed Zha, a doctor’s love letter that gives patients their voices back. If you enjoy it, please comment, like, share, and/or subscribe!

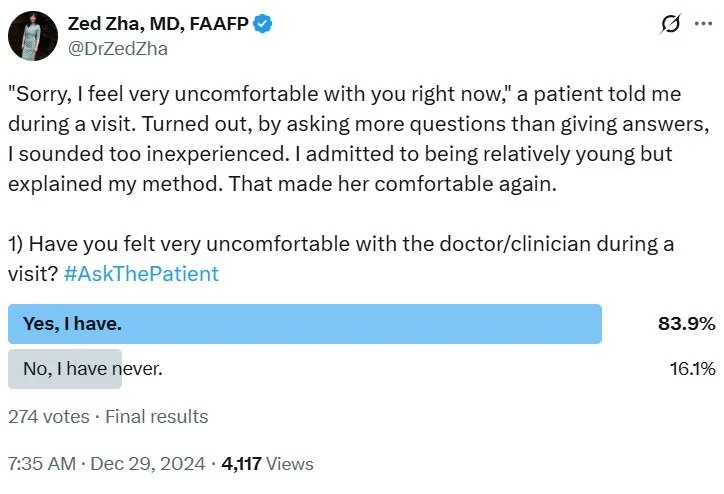

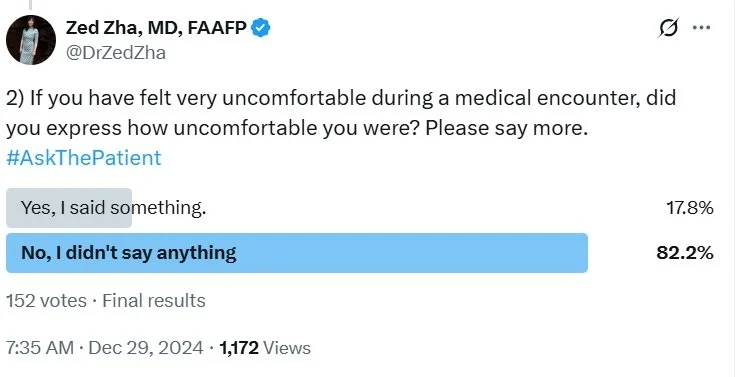

I try to make my patients comfortable with me, but it doesn’t always happen. Sometimes, people tell me, but mostly, they don’t.

The Uncomfortable Patient 1: Mario

Mario was a tall man in his early 50s. He had a mustache that he wore proudly — until a few weeks ago when he woke up with part of it missing. Eager to get his facial hair back, Mario came to his appointment almost a whole hour early.

“What do you think I have?”

“I think you have alopecia areata,” I answered. His symptoms are classic — waking up one day to see that a small area of the hair is completely gone, leaving the skin smooth and otherwise normal.

“What’s that?”

“It’s an autoimmune condition…”

Before I could finish, Mario puffed up his chest and protested: “I don’t think so.”

He went on to tell me his theory: recently, a small piece of rock flew onto his face while he was mowing the lawn. He felt that something must have gotten into the skin, which led to the hair loss.

“I see…” I wanted to explain that sometimes, physical or psychological stress, such as an injury, can certainly trigger an autoimmune response in our bodies. But, once again, I didn’t have time.

“What do you think this is, then?” Mario pointed to a small brown lesion on his forearm. Rather than a question, it sounded more like a test.

“It’s a solar lentigo,” I answered, my days of getting quizzed by my attending in medical school flashed back in my head, “it’s from the sun.”

“Nope,” Mario shook his head, “I haven’t been in the sun much at all.” He rolled up his sleeves, exposing his obvious tan lines at the elbows.

Before I could rebuttal, the next quiz came: “How about this, what’s this?”

Having learned my lessons, this time, I asked him what he thought it might be. A smile appeared on his face that said: Gotcha! You don’t know your stuff!

After the visit, I sat at my workstation to write notes. I frowned about what diagnosis to put down, because, clearly, we didn’t agree on them.

“Wow, that was awkward,” my medical assistant came out of Mario’s room at this time. Turned out, after I left, Mario asked her how long I had been a doctor. “She didn’t look like she knew what she was talking about,” he said, “and that made me uncomfortable.”

—————————-

Here are the thoughts that went through my head, in chronological order:

Defense: I do know what I’m talking about! He just didn’t agree with what I said!

Anger: Why don’t I look like I know what I’m talking about? Is it because of my age? Gender? Would Dr. Joe Smith’s competency be questioned like this?

Confrontation: I’m gonna go back there and ask him directly!

Deep breath: Wait, but is that going to change anything? It’s not like he called me incompetent to my face.

Curiosity: He was a big, confident guy, why didn’t he tell me to my face? And, does it matter who was right and who was wrong? Is that what patients come to us for? Also, I noticed that as he “quizzed” me, I sped up the visit in an effort to “escape.” Did he really quiz me or was he simply asking me questions? Did my trauma in medical education of being publicly shamed for not knowing the answers affect how I responded to him?

Reflection: Ultimately, the result was my patient didn’t trust me. And I know, as much as anyone else, trust is essential to healing. More importantly, even a confident guy like Mario didn’t feel comfortable telling me in person that he was uncomfortable, which cost me the opportunity to make things better for him. Imagine how many other patients have felt this way and I had no idea!

Growth: If given the chance, I would slow things down, stay with the uncomfortable moment, and invite people to help me do better.

I know what you are thinking: Zed, tsk tsk, a mature human being! 😎

Not really.😅

The truth is these came to be in painful intervals throughout the days following the incident. And within each interval, the paper castle of who I was as a physician fell apart. And maybe I am still rebuilding it as I write this newsletter. But I think that is OK.

The Uncomfortable Patient 2: Tracy

Tracy was a young woman in her late 30s. She had a small thing on her cheek called sebaceous hyperplasia — the overgrowth of an oil gland — that she would like me to remove. A few years back, she had another one that a clinician in another state removed. She liked the result.

Here is the thing about destroying lesions on the face: it’s tricky. Too gentle — it doesn’t work. Too aggressive — you can give people a scar. And unlike in the armpits, scars on the face are a big deal. And everyone’s skin is different. It’s hard to predict who will scar and who won’t. So, my approach to the face is to air on the gentle side. But this wasn’t Tracy’s first rodeo. So, I thought, why not ask her what worked for her before?

“How was it treated the last time?”

“Well,” Tracy raised one eyebrow and tilted her head, “they burned it.”

“How did they burn it?” Sometimes, people think of freezing with liquid nitrogen as “burning,” and other times, they consider electricity as “burning.” I thought I would ask her to clarify.

“What do you mean?” She crossed her arms.

“I mean, did they use liquid nitrogen, which would be cold, or electricity, which would feel like a light zap?”

“I don’t know.” Tracy now crossed her legs, too.

“Ok,” I thought I’d try asking in another way, “Did you develop a blister after?” What I meant was that liquid nitrogen can make people’s skin blister — like a frostbite. And if she had a blister, that would give me a clue what they did.

Tracy’s eyes narrowed, her arms and legs were still crossed. I wasn’t entirely sure what was going through her mind. But her body language gave me a clue — she didn’t understand why I asked her so many questions about what was done before. Of course, I thought, I ought to explain myself. My explanation was going to start with “I’m sorry that…” but Tracy beat me to it.

“I’m sorry. I am really uncomfortable with you right now.” The word “really” was really emphasized.

For a very brief second, I thought Tracy was feeling physically sick. Then I realized what she voiced was not physical.

“You don’t sound very experienced at all. You keep asking me how they did it,” Tracy was sitting in a chair in the corner of the exam room. Now she unconsciously curled herself back into the corner, “It sounds like … you’ve never done this before.”

The patient was uncomfortable with me.

—————

Up until now, I could count on one hand the times when a patient felt “comfortable” enough to tell me they were uncomfortable. However, I am not entirely oblivious (though I think perhaps many are) to the fact that patients often feel uncomfortable with doctors or other healthcare workers. They just don’t tell us.

All you have to do is #AskThePatient.

Why don’t people tell their doctors when they feel uncomfortable?

First of all, doctors are people (we hope), too. And some people make others uncomfortable. And patients are people, too. They might not be the confrontational type.

Secondly, the steep power dynamic in a doctor’s office prevents people from speaking their minds, in general. They might not want to challenge the “white coat authority;” they might not want to hurt our fragile egos; or, they might not feel empowered to disagree with us for fear of retaliative treatment.

Not the last and definitely not the least, if patients don’t feel comfortable with a doctor, whose help they need for their well-being, sometimes for matters of life and death, then they literally don’t even feel safe. How can someone scared for their safety feel comfortable enough to speak up?

But Tracy did.

And what courage it took. 🩵

If given the chance, I would slow things down, stay with the uncomfortable moment, and invite people to help me do better.

Even though Tracy and I were about the same size, the atmosphere in the exam room felt as if I occupied most of the space, casting a big shadow over her, and making her smaller, and smaller.

“I see,” I backed myself away from Tracy’s space, walked to the stool, and sat down. We were now at the same eye level. “You are right, I am not very experienced in this.”

To be honest, I was a little surprised to hear myself say that. Medical education teaches you to puff up and don’t back down. To fake it until you make it. Now I was doing the opposite of what I was taught.

I prepared for the worst.

But strangely, Tracy uncrossed her legs and inched forward in her chair. I took the gesture as a “ok, I will hear you out.”

“I am not well-trained in cosmetic procedures like this,” I continued cautiously, observing Tracy’s body language. “So, I wouldn’t say that I’ve taken off hundreds of sebaceous hyperplasia.”

Her arms are now uncrossed, too: “Would you feel more comfortable if I went somewhere else for this?” She asked. It was a question that, in the past, would sound like a challenge. But now, when I really listened to her tone, it sounded genuine and even…caring. Like she was making sure I was comfortable.

“Well, but I have taken off dozens of them,” I continued, understanding that “dozens” didn’t sound like a lot. But it was the truth. “So, I am not uncomfortable doing it. But I don’t want to make you uncomfortable with having me do the procedure. So, I totally respect your choice.”

Tracy had now moved her body back to the center of the chair, coming completely out of the corner. My big, intimidating, imaginary shadow retreated and dissipated.

I went on to explain the logic behind my asking more questions than giving answers. I told her that I believed there were multiple ways to do anything in medicine, and sometimes, the best way was what had worked before. I could tell, as I continued, Tracy became disarmed.

“Can I tell you how I would do it?” I asked.

“Sure!”

After describing my method, I emphasized again that I wouldn’t be offended if she decided to go somewhere else for her care.

“Hmm,” Tracy’s face softened, “I guess I shouldn’t have questioned you.”

“Why shouldn’t you?” I smiled. “Of course you should! I would have if I were you! It’s my face — that’s my money maker!” I joked.

“Exactly!” Tracy giggled.

Eventually, she decided to stay. I invited her to “monitor” me with a mirror to make sure she was comfortable with every step. She accepted. I explained what I did as I went along. At one point, Tracy told me she worked remotely as a computer scientist.

“So, I guess my face isn’t my money maker!” Tracy laughed, “But it doesn’t hurt to look fabulous, right?”

Turns out, it doesn’t hurt to get some patient feedback, either.